Simplifying Complexity – Part 1

“Why did they have to make this so complicated?”

We’ve all said or thought this as we sat in front of a computer screen, struggling to perform a task but unable to figure out how to do it. Frustrated, we wish the software could be made simpler to better accomplish the task at hand.

Modern software can be complex, and Part 1 of this series will take a look at some of the forces that drive complexity and thwart simplicity, and why complexity cannot be completely avoided, but instead must be dealt with more effectively. In Parts 2, 3, and 4 of this series we will look at design guidelines and techniques that software developers can use to help manage complexity, to create a simple user experience in complex software. Note that these articles will focus on managing the complexity of the user experience, not the complexity of the source code itself.

Simplicity

Software interfaces can be simple. For example, I have a timer app on my smartphone that’s quite simple; it performs a simple task and doesn’t need a complex interface:

Other factors drive simplicity. In some cases, functionality has been intentionally restricted. Perhaps the application was developed on a budget, or as someone’s side project. Keeping it simple reduced development time, QA time, customer support, and so on. Or perhaps the developer offers a free version of a product with limited functionality, and a paid version with the additional features. Or perhaps the software is an early iteration and the designer is planning on adding features and complexity as the product evolves.

Complexity

But these are the exceptions. There are many other factors that drive software to be more complex, and successful software is frequently complex software.

Software is often complex because it needs to be: as Einstein (supposedly) said, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”[1] Consider Mathematica, which has nearly 5,000 built-in mathematical functions and tackles problems like matrix manipulation, computational geometry, and finite element analysis. The problems aren’t simple, so Mathematica isn’t simple. For example, here is a Mathematica dialog box with three levels of tabs.[2] I’m showing this dialog box as an example of real-world complexity; I’m not criticizing or defending the UI.

A related factor is that features sell software — and drive complexity. Mature software products have evolved over time, with more features in each version. Mathematica, to take one example, is currently in Version 10. Adobe Photoshop is a classic example of feature-drive complexity being exacerbated as a product evolves, in this case since 1990.

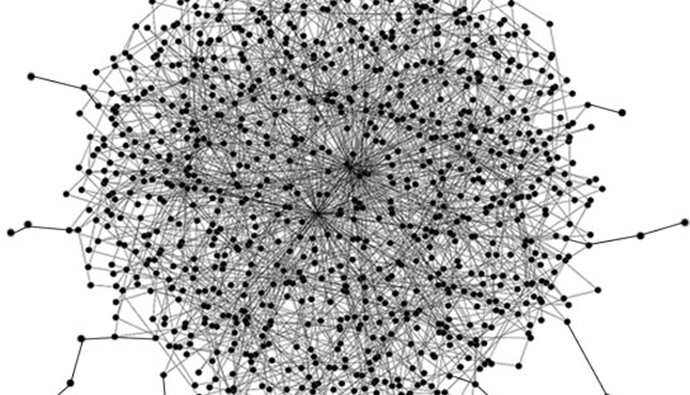

We also live in an increasingly interconnected world, where setting up communication between different applications and environments is expected and further drives software complexity. An Apple Watch requires an iPhone. I can dock my iPhone in my car and play music using dashboard controls. A household thermostat is connected to the internet. We have Wi-Fi in our homes. Third-party apps can show calendar appointments from Microsoft Outlook and Google Calendar in one place. This list goes on, and will only grow.

This interconnected world contains threats. Firewalls, anti-virus software, pop-up blockers, passwords, and the need to be vigilant against phishing and to protect our privacy add additional layers of software and behavioral rules — and, of course, complexity.

Simple Complexity

Do we want simplicity or complexity? Consumers and businesses have responded to this dichotomy pretty clearly — we like feature-rich, complex software. That’s what we buy. Donald Norman, the famous design and usability expert, says, “Simplicity is not the goal. We do not wish to give up the power and flexibility of our technologies.”[3] If we want simplicity and buy complexity, the issue becomes how to simplify that complexity.

Consider Photoshop again. It is a great product; I use it and like it very much. That said, Photoshop is very complicated software. Many a novice has wondered into a world of layers, filters, paths, and channels, and left frustrated at the inability to perform what seemed like a simple task. It’s fair to say that Adobe hasn’t put a lot of focus on simplifying that complexity and that their audience of design professionals is willing to invest the time to learn Photoshop as a fair trade for its immense functionality. The same could be said for applications like Autodesk AutoCAD and many others.

But what Adobe has done is released a simpler, companion product for a subset of Photoshop users — photographers. It’s called Lightroom, and it is built on Photoshop technology (specifically the Camera Raw processing engine), but Adobe did two things with Lightroom. They eliminated many image processing features that photographers seldom use (while adding some features that photographers needed). They also completely redesigned the interface to map the user interface to the process that photographers use when working with images. The result is a much simpler product that is intuitive to photographers.

Apple’s iOS, on the other hand, was simple and intuitive out the gate, and is likely to remain that way. Once you learn how to do a few things on iOS–swipe, launch apps, access settings–everything else seems to fall into place. You learn quickly and it seems, well, simple.

These are two success stories. Part 2 of this series will look the various ways that such successes can be accomplished, as we examine some of the design techniques that human factors engineers and user interface designers use to simplify complexity.

Dr. Craig Rosenberg is an entrepreneur, human factors engineer, computer scientist, and expert witness. You can learn more about Craig and his expert witness consulting business at www.userinterfaceexpertwitness.com